The Marconi Wireless Station at Juneau, Alaska

by Bob Rydzewski, Deputy Archivist, CHRS

and Bart Lee, Archivist, CHRS

“Wireless conditions existing in Alaska are not to be found elsewhere,” according to Wireless on the Pacific: A Record of Continuous Growth (Wireless Age, Vol. 1, 1913). “Southern Alaska is made up of vast wooded mountains and the rainfall is heavy. While a station is often able to communicate 1000 miles in one direction, it is sometimes unable to communicate any reasonable distance in another. For this reason it is necessary to give careful study to the location of the stations. It is believed that a 25 K.W. station at Ketchikan and a 10 K.W. station at Juneau will assure continuous communication between those points and Seattle… The Marconi Company intends to act quickly in placing wireless communication throughout this country after it has once been established that a station at a certain point can be depended upon to carry out its requirements and prove to be the source of a reasonable amount of revenue. The stations at Ketchikan and Juneau will be among the first to be constructed.”

Arthur A. Isbell, Pacific Marine Review, Vol. 15, August 1918

Arthur A. Isbell, Pacific Marine Review, Vol. 15, August 1918

The man who would build the Marconi Juneau station was Arthur Isbell. According to an article in the Marconi Service News (Vol. 2, May 1917) Arthur learned telegraphy as a boy and had been a schoolmate of Lee DeForest. He became a General Manager at the original DeForest Company, joined the Massie Company in 1906 and while employed there equipped and operated on the first ship with wireless to sail the Pacific (the S.S. President). He later designed and built a 10 K.W. spark station at Kahuku, Hawaii for the Wireless Telegraph Company, Ltd., became New Orleans Division Superintendent for United Wireless, erected the first wireless station in New Zealand, and finally threw in his lot with Marconi, where he became a construction engineer and was shipped off to build the Alaska stations. Yes, quite a distinguished career, with more to come at RCA.

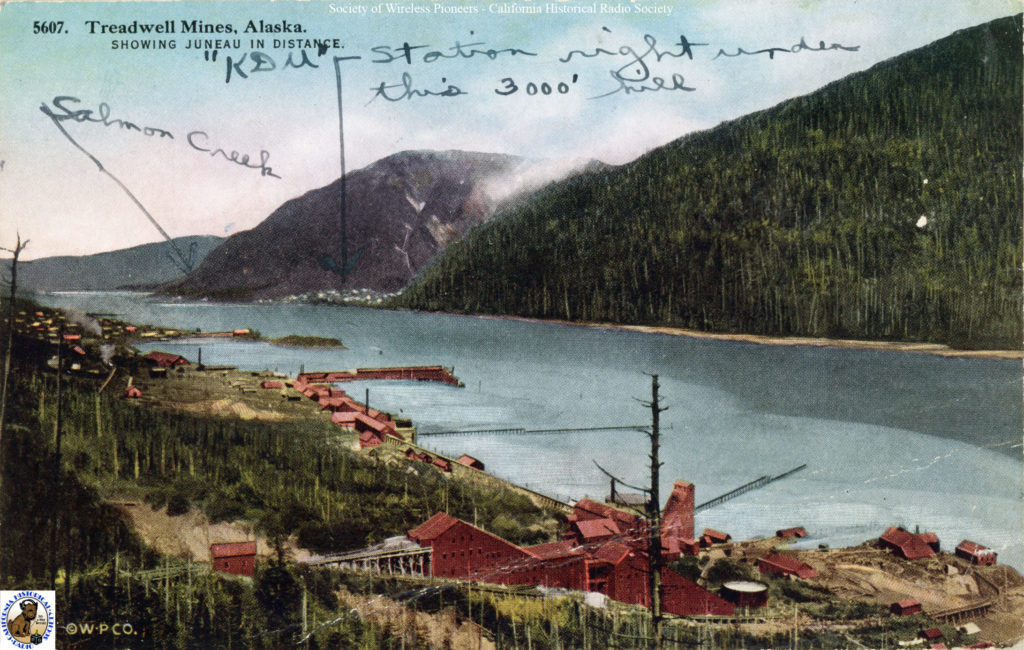

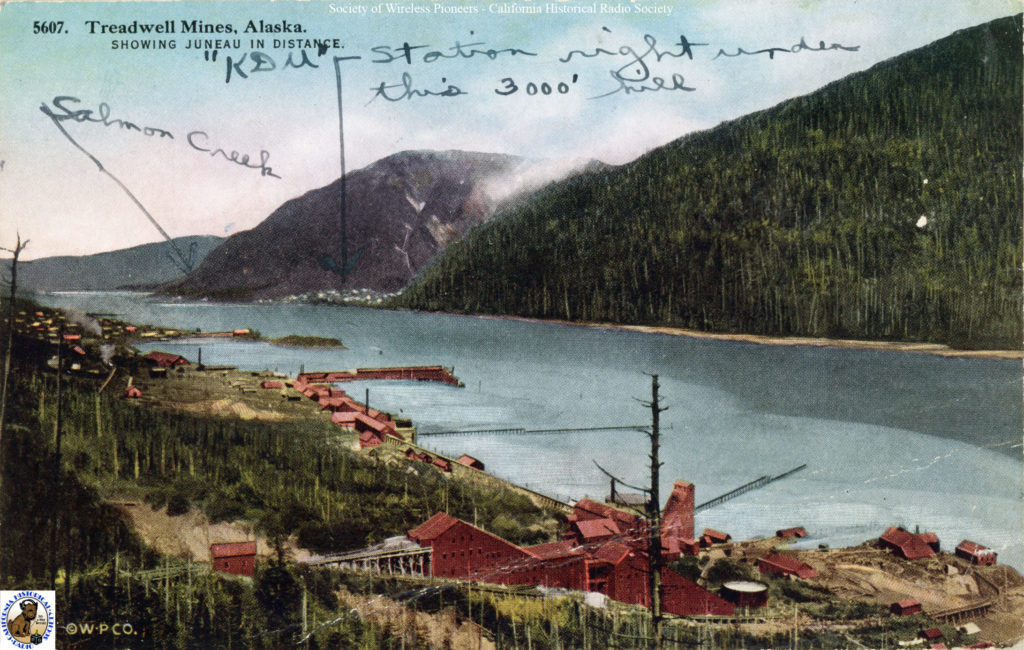

United Wireless had a commercial station (DU) at Juneau by 1910[1] that Isbell may or may not have built prior to the Marconi takeover of the company and its employee in 1912. How much of the Marconi station was really left over from United Wireless is unclear. The Marconi station (KDU according to Bob Palmer [SGP-61] who worked for Isbell)[2] as profiled by C.E. Bence in the 1917 Marconi Service News does suggest that at least parts of it were really left over from United Wireless. “While not of the latest type [it] is an efficient station. It is situated on a hill beside Mount Juneau about one mile and a half from Juneau. The apparatus is chiefly of the old United type, Leyden jars are used for condensers and the transformers are of United design. The set as it is assembled is approximately 10 k.w. For receiving, a type 101 Marconi receiver is used. Juneau Station is the northern terminal of the Marconi Alaskan Circuit and in addition to this is used as a Marine station, clearing ships and also handles the traffic from the two leased stations, one at (KDN) Kensington Mines Company,[3] and one at (KJA) Jualin Mines Company,[4] thirty-one hundred meters [97 kHz] being used on the Alaskan Circuit, and with outlying stations, while 600 meters [500 kHz] are used in clearing vessels at sea.” Bence notes that, interestingly, “on cold, clear nights many freakish receptions are recorded. The Marconi Station at Bolinas, Cal. can be heard very well any time day or night. Honolulu and Japan at any time of night. Nauen, Germany and Sayville have both been heard at Juneau.”

Up until now, little additional information was available on the Marconi station at Juneau. A recent “dig” through the Society of Wireless Pioneers archives, however, uncovered an interesting album apparently compiled by Isbell himself. Entitled, “JUNEAU ALASKA ENGINEERING FILE, INSTALLATION AND PICTURES. FURNISHED BY EARL W. BAKER (ORIG. BY A.A. ISBEL, ENGR. 1914),” we hereby present the photos therein for your information and enjoyment.

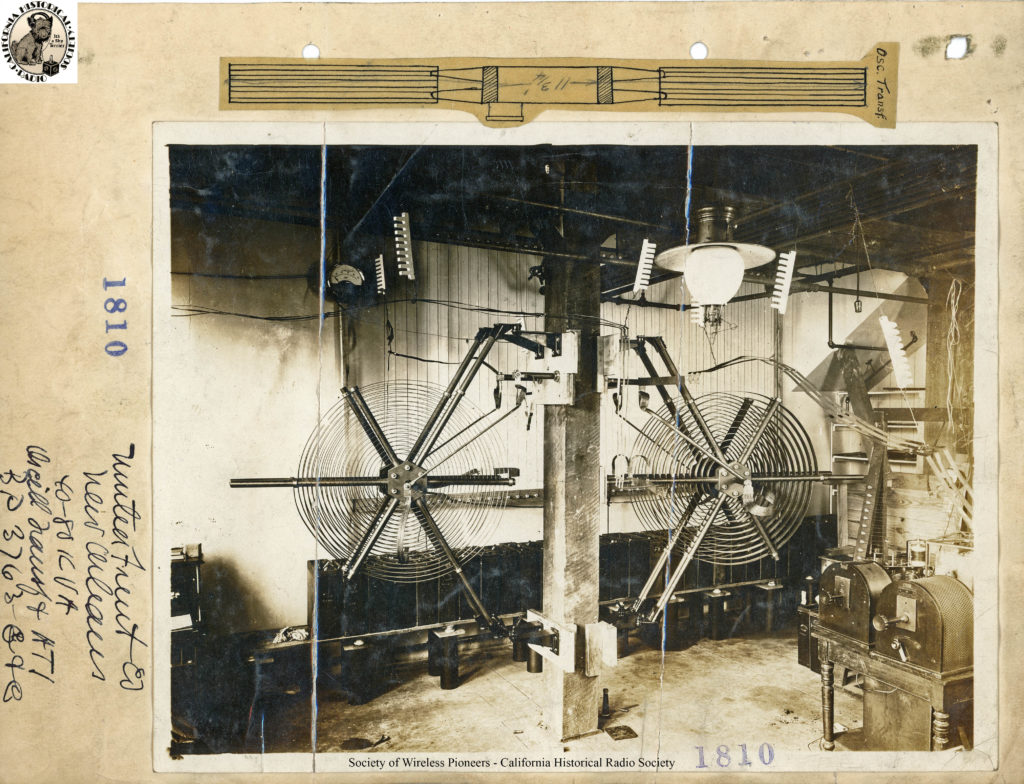

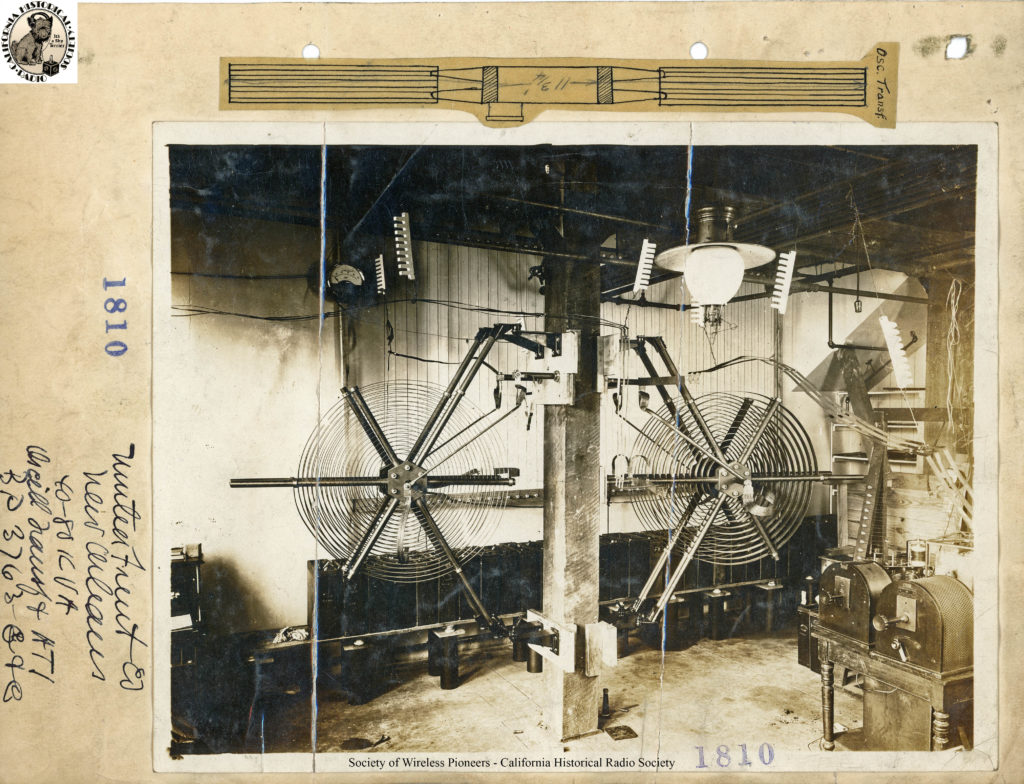

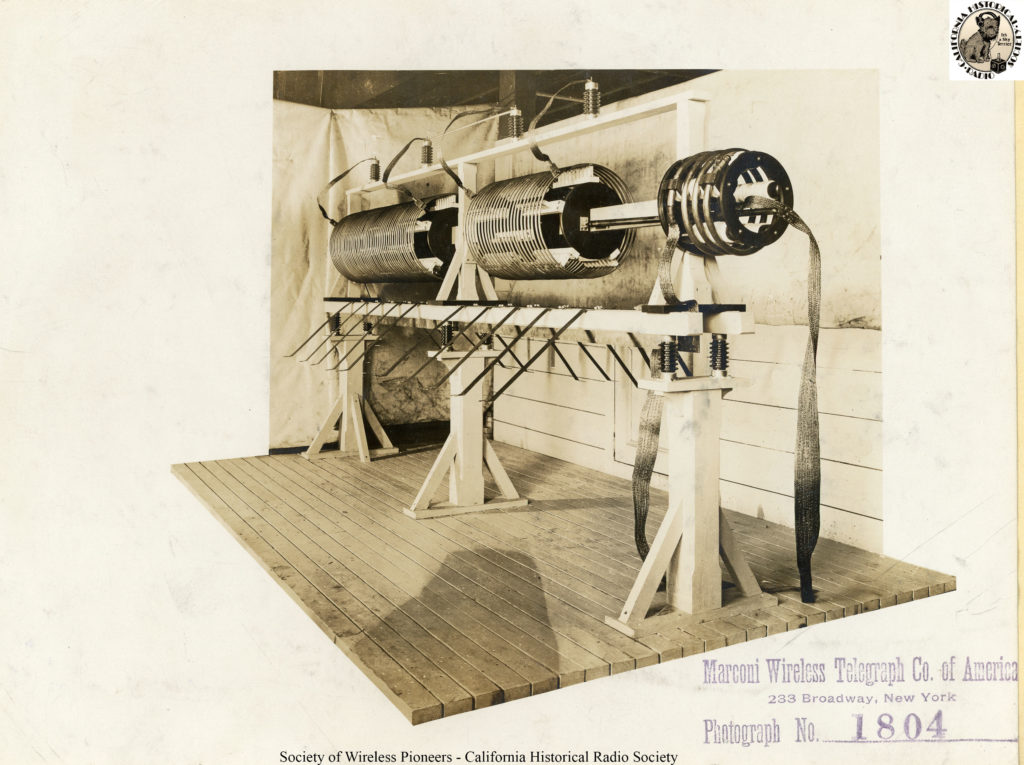

Page 1: “United Fruit Co. New Orleans 40-80 KVA Oscill Transf & ATI”

Page 1: “United Fruit Co. New Orleans 40-80 KVA Oscill Transf & ATI”

It’s not obvious why the New Orleans United Fruit Co. oscillation transformer was included in the Juneau scrapbook. Was Isbell comparing it with the more well-constructed Marconi one that follows?

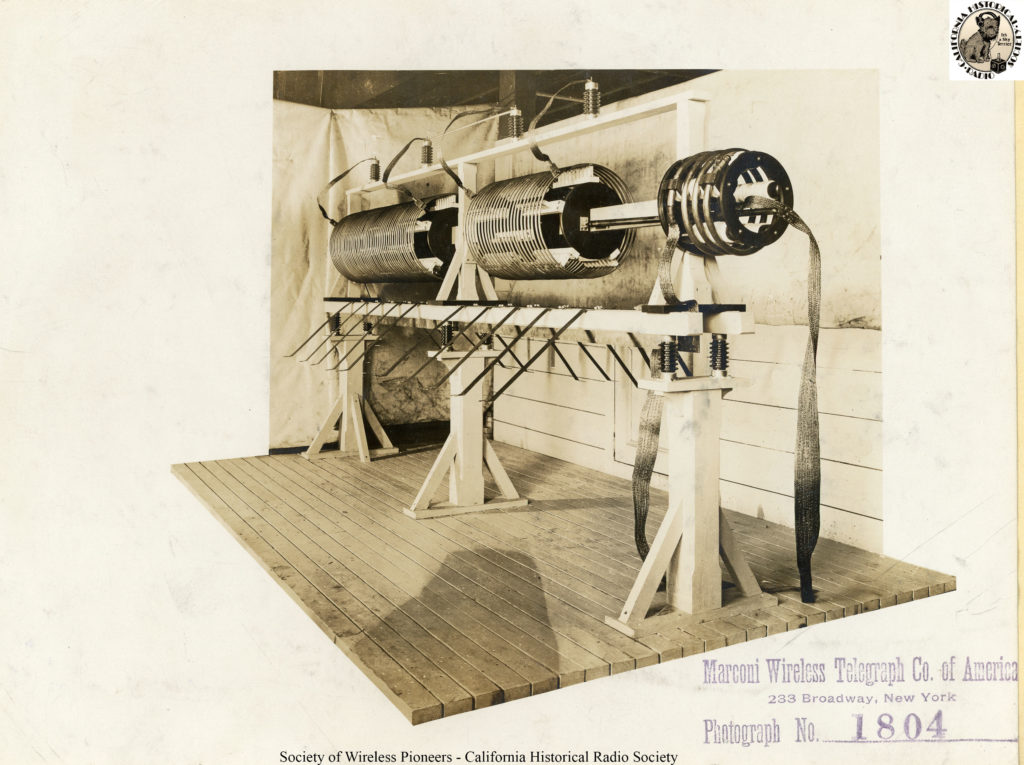

Page 2: No caption.

Page 2: No caption.

A couple of black-and-white landscapes of Juneau and environs in 1915 follow, some with engineering comments penciled in, apparently by Isbell, who frequently photographed sites and equipment.

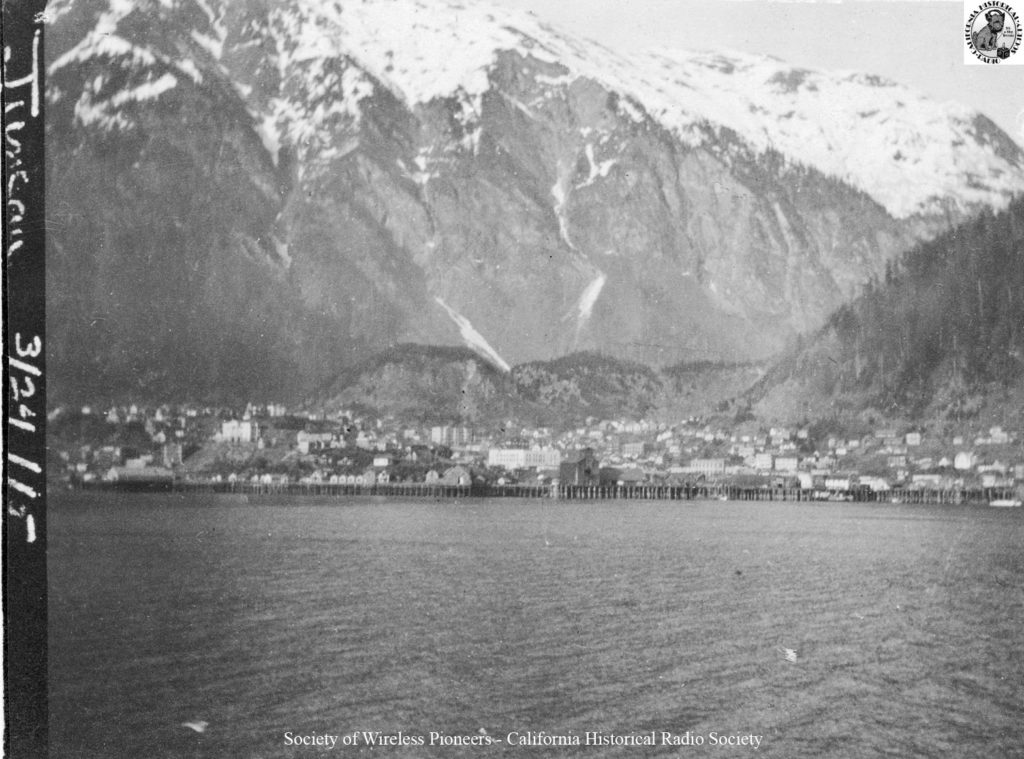

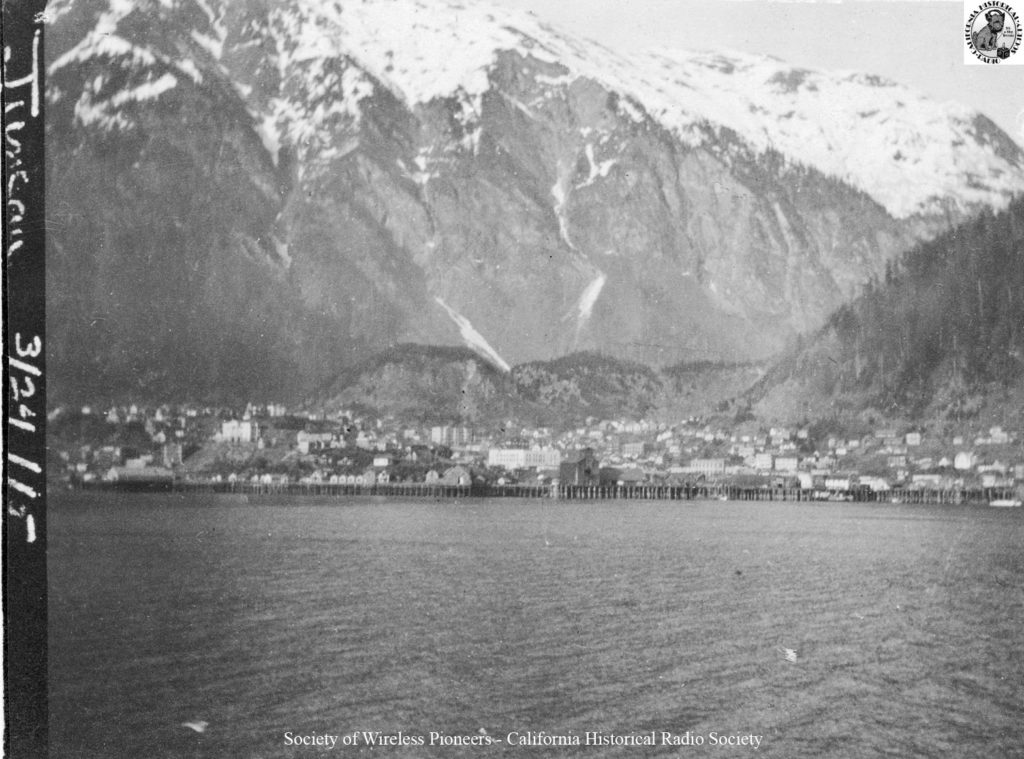

Page 3: “Juneau, Alaska, March 24th, 1915. View from Douglas Dock. A.A.I.”

Page 3: “Juneau, Alaska, March 24th, 1915. View from Douglas Dock. A.A.I.”

Page 4: “Juneau”

Page 4: “Juneau”

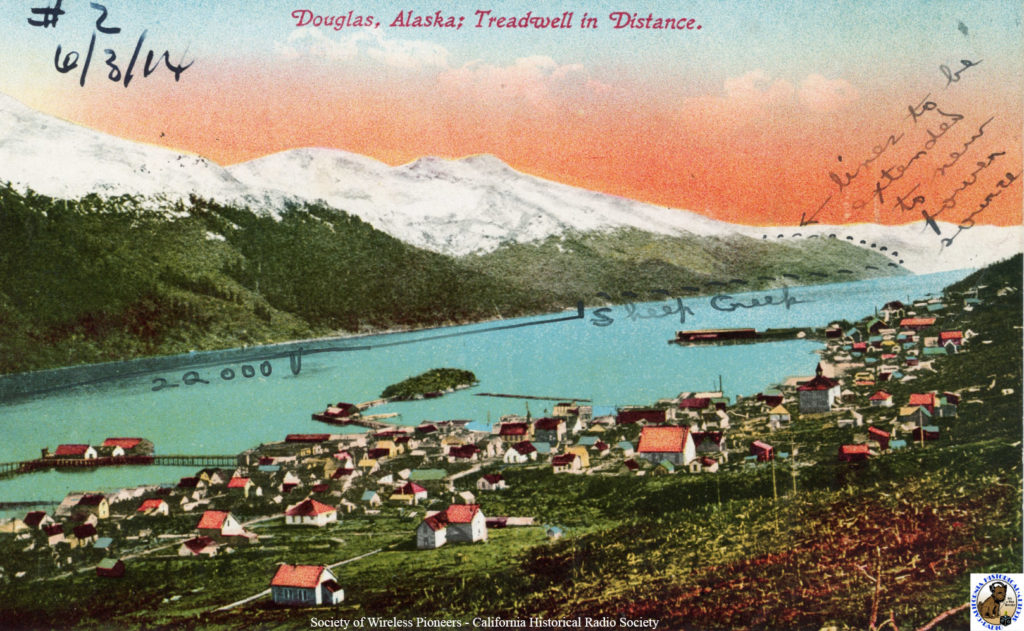

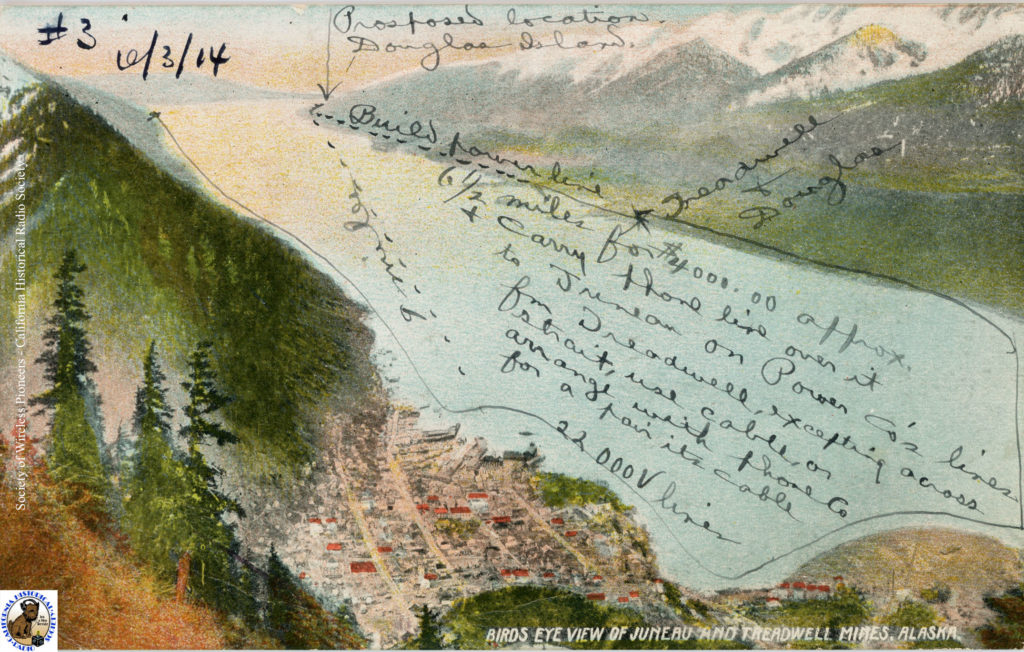

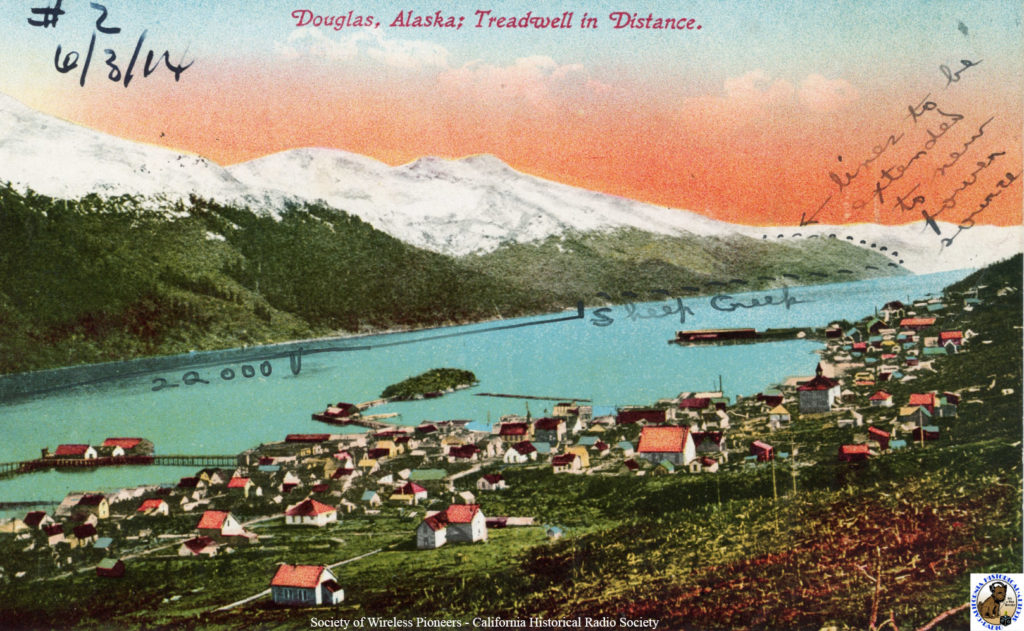

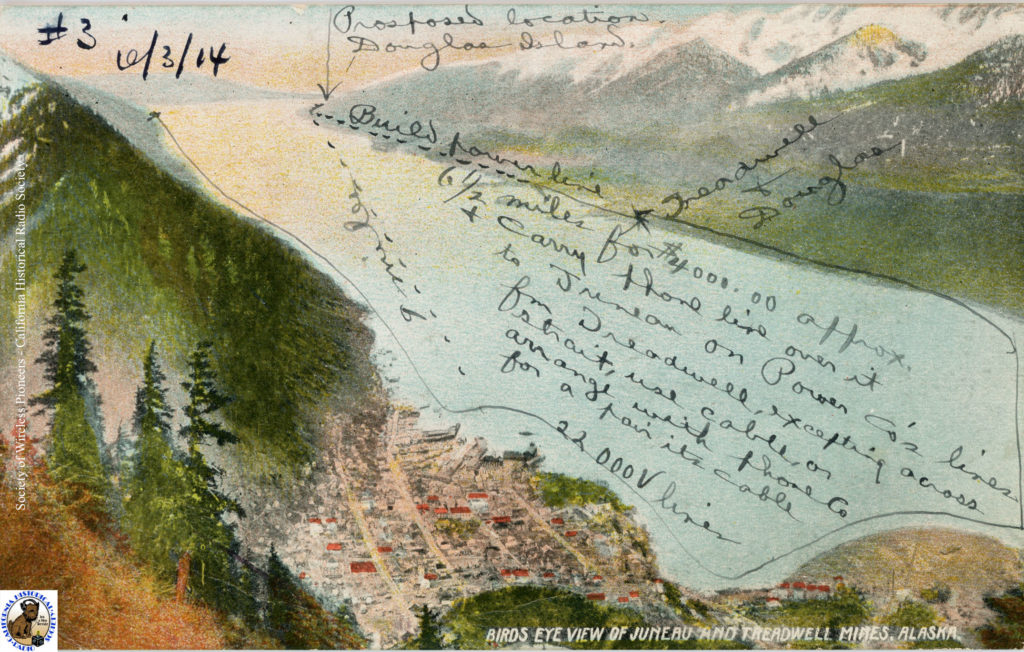

There follows a series of 4 remarkably vivid color postcard photos in which Isbell has penciled in details of how the 22,000 V power lines were to be brought to the station.

Page 5 #1: “Gives an idea of the character of the country. – A.A.I.”

Page 5 #1: “Gives an idea of the character of the country. – A.A.I.”

Page 5 #2: No caption.

Page 5 #2: No caption.

Page 5 #3: “Write you fully when get data & typewriter. A.A.I.”

Page 5 #3: “Write you fully when get data & typewriter. A.A.I.”

Page 6: No caption.

Page 6: No caption.

Notably, the Treadwell Mines shown above at one time employed over 2,000 people, was the largest gold mine in the world, and had extracted over 3 million troy ounces of gold before it closed in 1922. Information on the back of the postcard above notes that ore was treated using the cyanide process. Today not much is left of the Treadwell mine (and hopefully of the cyanide), but the good news is that several remaining buildings and much of the site’s history has been preserved and restored by the Treadwell Historic Preservation and Restoration Society, Inc.

Page 7: “Outskirts of Juneau from 1000 ft. up Mt. Juneau”

Page 7: “Outskirts of Juneau from 1000 ft. up Mt. Juneau”

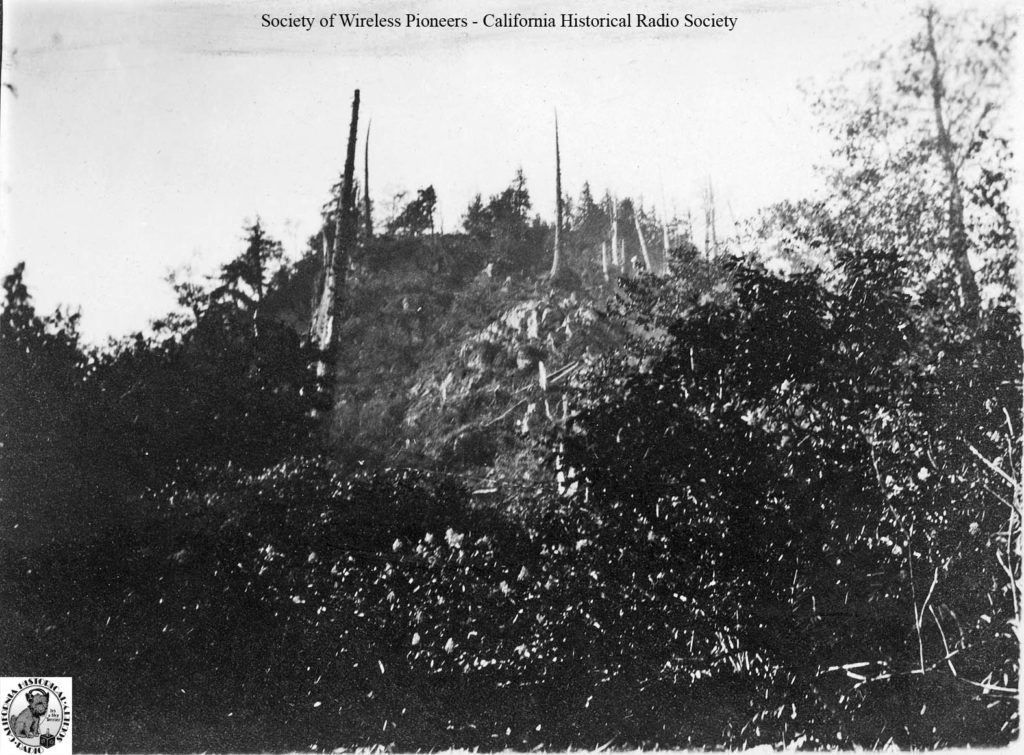

Page 8: “Juneau, Alaska. Shows bluffs and cleared space. A.A.I.”

Page 8: “Juneau, Alaska. Shows bluffs and cleared space. A.A.I.”

The scrapbook ends with a 1904 USGS topographical map of Juneau and vicinity, not copied here. Although we wish that more notes and text were left to SoWP, this photo documentation is truly unique. And who knows if more documents and photos from Isbell on KDU remain to be found in the many still unexplored boxes of the archives?

As for Arthur Isbell, he later became a General Superintendent at RCA and a member of the Veteran Wireless Operators Association (VWOA). He became a silent key in 1953,[5] a full 15 years before the founding of the Society of Wireless Pioneers.

CHRS Archivist Bart Lee has compiled more information about Arthur Isbell and his many adventures in his article “West Coast Wireless Comes of Age, 1899 – 1920” here. The colorful story of his early years in San Francisco, including getting shot at, most likely by rival United Wireless miscreants, is available at Bart’s 2011 Pacificon presentation, “They Tried to Kill Me”.

Thanks are due to Earl W. Baker (110-P) and, as always, the folks at CHRS and the Society who made the preservation of these historical documents possible.

[1] See The Pacific Aerogram, September 1910, p. 2, and Mariner, EH, “West Coast Call Letters Before 1910”, Sparks Journal, Vol. 4 No. 4, p. 7.

[2] See “Historical Notes from the Wireless Pioneers,” Ports O’ Call, Winter Edition 1968-1969, p. 22.

[3] A gold mine ~40 miles from Juneau that is still apparently in use today.

[4] A gold mine ~40 miles from Juneau, long defunct.

[5] According to Richard Johnstone in My San Francisco Story of the Waterfront and the Wireless (World Printing Service, Sebastopol, CA, 1965), p. 124.

Arthur A. Isbell, Pacific Marine Review, Vol. 15, August 1918

Arthur A. Isbell, Pacific Marine Review, Vol. 15, August 1918 Page 1: “United Fruit Co. New Orleans 40-80 KVA Oscill Transf & ATI”

Page 1: “United Fruit Co. New Orleans 40-80 KVA Oscill Transf & ATI” Page 2: No caption.

Page 2: No caption. Page 3: “Juneau, Alaska, March 24th, 1915. View from Douglas Dock. A.A.I.”

Page 3: “Juneau, Alaska, March 24th, 1915. View from Douglas Dock. A.A.I.” Page 4: “Juneau”

Page 4: “Juneau” Page 5 #1: “Gives an idea of the character of the country. – A.A.I.”

Page 5 #1: “Gives an idea of the character of the country. – A.A.I.” Page 5 #2: No caption.

Page 5 #2: No caption. Page 5 #3: “Write you fully when get data & typewriter. A.A.I.”

Page 5 #3: “Write you fully when get data & typewriter. A.A.I.” Page 6: No caption.

Page 6: No caption. Page 7: “Outskirts of Juneau from 1000 ft. up Mt. Juneau”

Page 7: “Outskirts of Juneau from 1000 ft. up Mt. Juneau” Page 8: “Juneau, Alaska. Shows bluffs and cleared space. A.A.I.”

Page 8: “Juneau, Alaska. Shows bluffs and cleared space. A.A.I.”