Pioneer Portraits: Arthur Enderlin, 183-P

“Whatever the problem, war is never the answer.” So taught Society of Wireless Pioneers member and U.S. Navy Captain Arthur Enderlin to his children. Having served his country both in the military and as a Defense Department civilian employee for many years, Captain Enderlin could not be accused of lacking perspective on this.

Born to Swiss immigrant parents in the Michigan Upper Peninsula town of Calumet in 1902, even a high school education for Arthur, their oldest son, was beyond their means. Instead, he needed to work at an early age. Lack of formal education has never implied any lack of intelligence and resourcefulness, and he proved to be quick-witted and a quick learner at the then-new science of radio communications, where he found a job. Besides radio, Enderlin proved to have a natural talent for games, puzzles, languages (he spoke 5), codes, and ciphers, a combined skill set that fit hand-in-glove with the unique role he would end up playing in communications history.

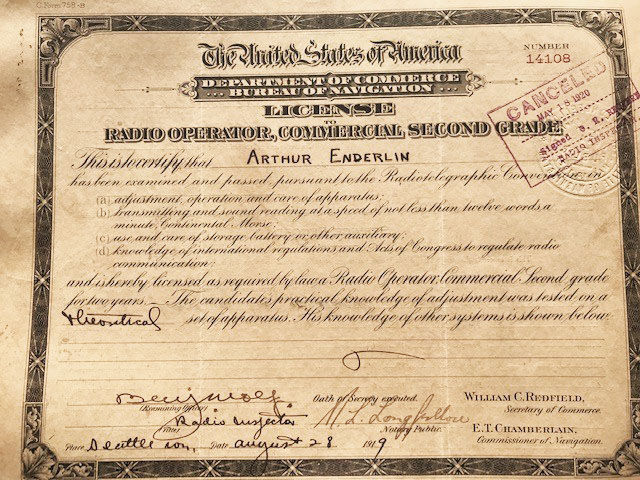

By the age of 16 Enderlin had developed a good “fist” for Morse code, and would go on to win speed and accuracy awards. In 1919 he received his first commercial “ticket” and soon went to sea as a radio operator on ships (the first being the SS Aspenhill) sailing to Central America, Europe, and Asia.

Fortunately for us, Enderlin was an early “shutterbug”. At a time when photography involved considerable expense and dedication—not least of which involved toting film, negatives, photos, and paraphernalia around through typhoons, battles, and blizzards—he carried his Leica wherever he went, leaving a legacy of thousands of carefully filed and annotated photos that document faraway places and long-ago times. His many photos, in fact, are currently being curated by his daughter, Dr. Allyn Enderlyn, who is pursuing permanent archival housing for the collection. We at SoWP were fortunate that she contacted us recently, providing much of the information and all of the photos in this article.

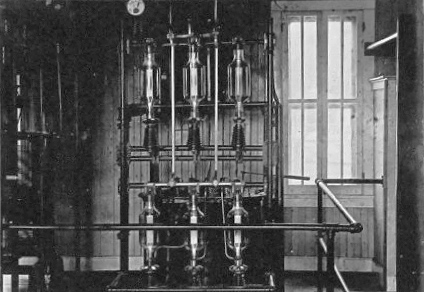

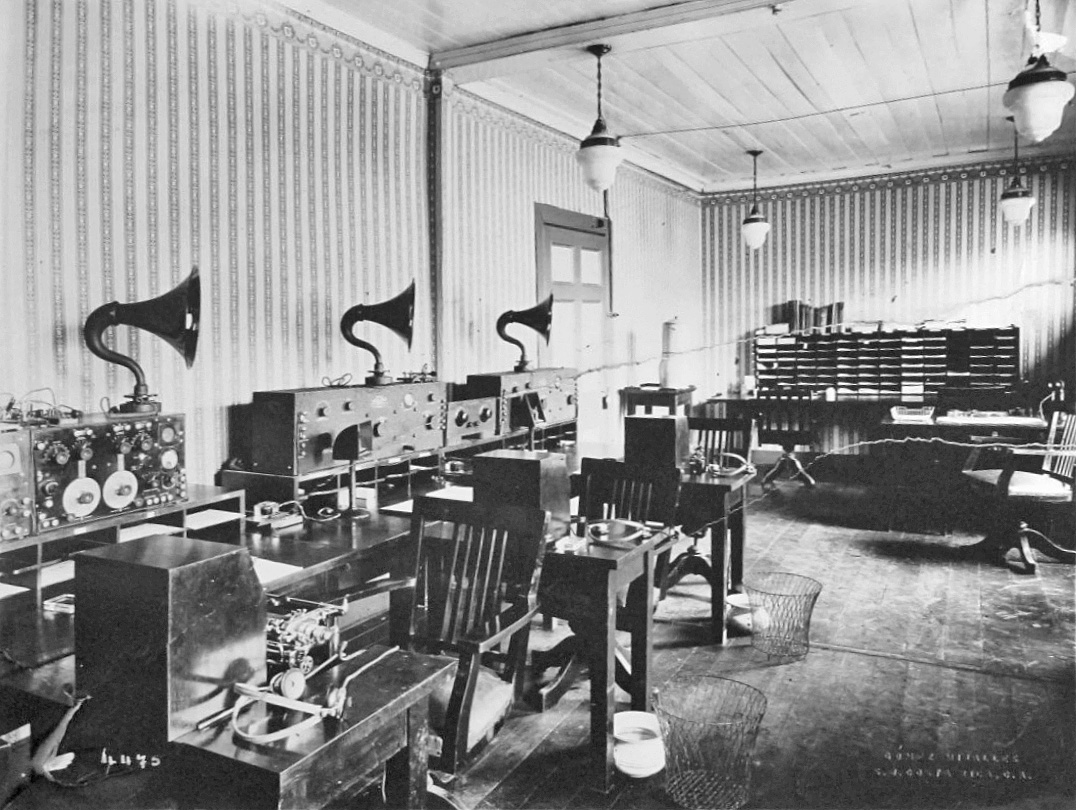

After nearly 10 years aboard more than a dozen ships as well as brief stints at shore stations (KGH/KEK in Portland, Oregon and KFS in San Francisco), Enderlin was hired as a radio engineer by The Tropical Radiotelegraph Company, a subsidiary of the United Fruit Company, which controlled the lucrative banana market and accounted for much of the US commercial interest in Latin America. Among the stations he helped build was Almirante Radio in northern Panama. Its 1 kW master oscillator is shown in the second photo, and its 30 kW rectifier (15,000 V @ 2A) in the fourth photo below.

He also worked on (and photographed) station UR, located in San Juan, Costa Rica, shown below. Note the prominent horn speakers and convenient spittoons.

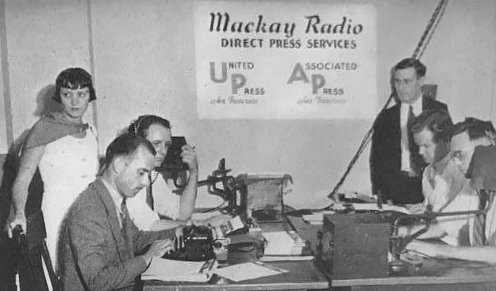

In 1928 Enderlin was lured away to the International Telephone and Telegraph Company (ITT), which owned an array of Latin American communications systems and soon acquired Mackay Radio. He would go on to spend the next 12 years at their regional center in Honolulu. In 1932 he was one of two speedy radiotelegraphers Mackay trusted to relay breaking developments in a trial that had transfixed both Hawaii and the mainland, the Massie murder trial. Mainland interest was so great that dedicated radio channels from the courthouse in Honolulu to San Francisco were established to get the United Press and Associated Press stories out at the speed of light, with minimal delays due to fist.

Enderlin had previously joined the Naval Reserve, most likely for the small supplement to his income that it provided. But in April of 1932 the U.S. Navy began to recognize his talents, commissioning him as an Ensign. Promotions to First Lieutenant and then Lieutenant followed a few years later. In 1940, as war clouds loomed on the horizon, he was called to active service at the main Naval Radio Center in—of course—Pearl Harbor. Through the “day of infamy”, about which he never spoke, and throughout the war in the Pacific, he remained with the Navy and served with distinction, first organizing the Naval Communications Office at Pearl Harbor, then as a communications officer in Saipan, Tinian, Guam, and Okinawa. He was promoted to Captain, a rank rarely obtained by those who had never attended the Annapolis Naval Academy, much less high school or college.

Not long after his return to post-war civilian life he was recalled to active duty by the Department of Defense and ordered to report for duty at the US government’s secret Communications Intelligence (COMINT) station at Arlington Hall, Virginia. This was followed by several years posting as Commanding Officer at the US Navy listening post in the welcoming clime of Adak in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands during the Korean War years of 1951-1953. In 1952, America’s cryptology organizations were unified under the aegis of a new organization, the National Security Agency (NSA). Even its existence was classified, and some claimed the initials must stand for No Such Agency! Captain Enderlin became the first Chief of the Office of Telecommunications at NSA, a position he held from 1953 to 1962. Among his accomplishments there were the establishment of a state-of-the-art communications system linking headquarters with NSA stations worldwide, SIGINT, and CRITICOMM, a system designed to get important worldwide news to the desk of the US President securely within 10 minutes.

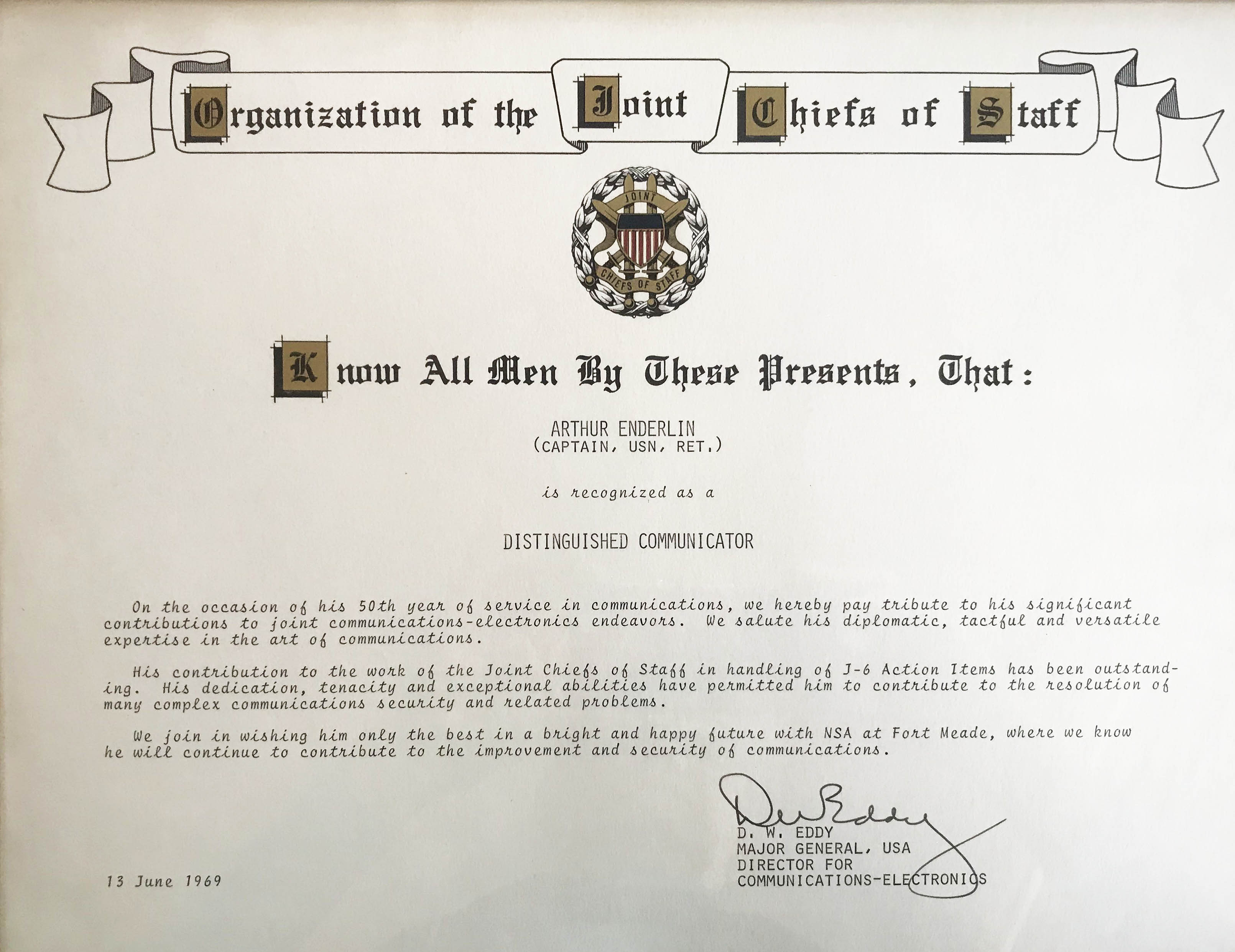

Even after his official retirement in 1962 the cryptology community and the US government did not want to see him go. He became a civilian Defense Department consultant for several more years. Although his experience had begun in the days of spark and arc, Enderlin was an impressively forward-looking thinker. A 1970 memo he wrote entitled “Why Digital?” argues for the implementation of digital technology at a time when most experts were still committed to analog transmission methods. He correctly predicting that aside from the advantages of easier encryption, with the use of timesharing and digital transmissions by narrow-bandwidth methods such as satellite, costs would soon be less than those of the older method. We haven’t asked the NSA, but it seems safe to assume that they ended up taking his advice. His professional service was recognized by many citations including an award from the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

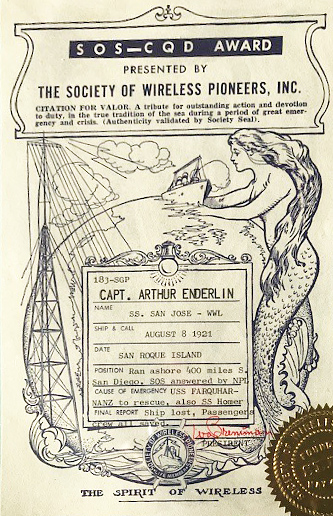

Arthur Enderlin was proud to be a member of the Society of Wireless Pioneers, and in the early 1970s he even presented a series of talks at their Washington D.C. chapter meeting that, tongue-in-cheek, he called “The Saga of Arthur Enderlin”. Much to our regret, we have found no notes, slides, or recordings of these presentations so far. But thanks to his daughter, we do have a photo of another award he received, this one from SoWP commemorating his wireless service when the SS San Jose ran aground 400 miles south of San Diego in 1921. His SOS summoned two US Navy destroyers and all lives were saved, though the ship could not be.

Captain Enderlin was also a member of the Veteran Wireless Operators Association and the Navy Cryptologic Veteran’s Association. In 1981, at the age of 78, he died of leukemia at the Bethesda Naval Medical Center.

From Morse code sent via sparks to digital codes via satellites, his career had run the gamut of 20th century communications technologies and paved the way for those of our own times. From ensuring the safety of merchant ships in stormy seas to signal interception meant to prevent the kind of unspeakable carnage he had seen at Pearl Harbor (“Whatever the problem, war is never the answer”), in the true Wireless Pioneer spirit his life had been all about protecting those of others.

Much more information about Captain Enderlin and many more of his photos are available on the website of his daughter, Dr. Allyn Enderlyn. We encourage you to peruse these at https://drallynenderlyn.com/archives/museum/.